Research Snippet #3: Lymphoma and COVID-19 Case Study

Welcome to our third CSM research review!

Given our recent masterclass on lymphomas and leukemias, I thought it the perfect time to look at how patients with these cancers are faring during this pandemic. Our previous article focused on a statistical overview of how cancer patients are faring, so I thought it would be a nice change to shift our focus to an individual patient who is immunocompromised and facing the threat of severe disease from COVID-19. It will also give us an exciting look at how COVID-19 treatment is constantly evolving.

On this topic, Hosoba et al. have recently published a case report about a 69-year-old woman in Japan with no medical history, who was diagnosed with an adult T-cell lymphoma—a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. She was started on a common chemotherapy regimen for non-Hodgkin lymphoma known by the memorable acronym “M-CHOP”; a combination of mogamulizumab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone. Her lymphoma went into remission, but she remained in an immunocompromised state, both from the lymphoma itself and from the chemotherapy, which both attacks CD4 T cells. Things were going well until day 15 of her 4th cycle of this chemotherapy when she developed a fever of 38 degrees, a mild cough, and a sore throat. Facing a case of febrile neutropaenia in an immunocompromised cancer patient—a potentially fatal red-flag presentation—she was started on levofloxacin as an empirical antibiotic, as we are usually most worried about bacterial infection in such patients.

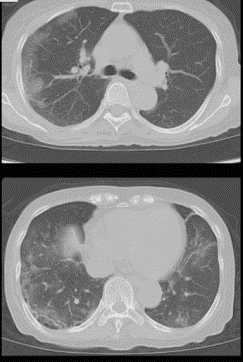

On day 20, she presented to Hosoba et al.’s hospital, now with a dry cough. Her fever had not subsided despite the antibiotics. Blood tests showed a low white blood cell count of 2,700//μL, with a CD4 T cell count of 23/μL indicating an immunocompromised state, and a high C-reactive protein (CRP) indicating an active inflammatory state. When a CT scan was performed, saw ground-glass opacities, which are typical of pneumonia caused not by bacteria, but by COVID-19 (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Bilateral and subpleural CT-scans showing ground-glass opacities that are typical of COVID-19 infection, taken by Hosiba et al. on admission.

Following this, she was admitted to hospital and started on further empirical therapy; piperacillin/tazobactam in case the infection was still bacteria, and voriconazole in case it was fungal. The following day, a COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab returned a positive result.

The hospital was faced with a COVID-19 infection despite there not yet being any standard-of-care for COVID-19, not to mention no standard of care for COVID-19 patients with immunosuppression by chemotherapy and T-cell lymphoma. Given this, she was given only supportive care including paracetamol and observed closely.

Five days later her fever was controlled, in part by the paracetamol, but her COVID-19 swabs remained positive. Concerned by her immunosuppressed state, Hosoba et al. offered to try treating the patient with favipiravir—an anti-influenza medication commonly used in Japan which inhibits the viral RNA polymerase enzyme—and she gave her consent. It was started that day, first at 1,600 mg twice daily, which was reduced after the first day to 800 mg twice daily.

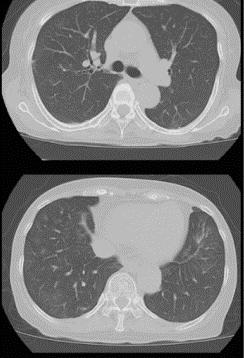

After the medication was started, the patient’s fever dropped rapidly despite no anti-fever medication being given, and her CRP also fell, indicating a reduction in the inflammatory state which makes COVID-19 so deadly. Five days into the favipiravir (10 days into the hospital admission), another CT scan was taken, which revealed a dramatic improvement, with the ground-glass opacities having reduced to a point where they are almost unnoticeable (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Bilateral and subpleural CT-scans showing a marked reduction in ground-glass opacities, taken on day five of favipiravir therapy.

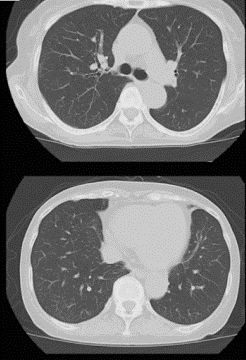

On day 10 post-favipiravir the COVID-19 remained detectable, so the treatment was continued for another four days. On days 17 and 18 the COVID-19 tests were now negative, so the patient wad discharged with no remaining disease on day 18 (day 23 in hospital). The fever had now resolved, and the CRP levels were down to normal, indicating a resolution of the inflammatory state. A final CT-scan was taken on discharge, which revealed complete resolution of the COVID-19 pneumonia (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Bilateral and subpleural CT-scans showing a complete resolution of the COVID-19 pneumonia, taken on discharge.

This research paper is particularly exciting since it was the first documented case of a patient with adult T-cell lymphoma who contracted COVID-19. It also offers favipiravir as an antiviral agent that is potentially effective against COVID-19 at a time where a reliable treatment has not yet been established.

However, as the authors of the study pointed out, the fever had already diminished before the favipiravir was administered, leaving it uncertain as to whether it was indeed the cause of the resolution of the pneumonia. Further studies and a large-scale clinical trial would be needed to determine definitively whether the benefit provided by the favipiravir was truly significant. Nonetheless, I hope this article gave you a small window into the challenge posed by COVID-19 in the care for cancer patients, the rapidly-evolving research into treatments for COVID-19, and the fact that we now all have one more differential to consider when confronted with a case of febrile neutropaenia.

If you would like to find out more, here is a link to a copy of Hosoba et al.’s paper: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jslrt/advpub/0/advpub_20030/_pdf/-char/en